On dark cold days when you seek your lover’s warmth by the window with a cup of tea, or when you feel that aching loneliness of being misunderstood, or when you feel detached from yourself and the pain and the heartache is almost crushing, poetry is the one thing that brings you peace. Poetry makes strangers fall in love, brings friends closer to family, and brings yourself closer to a more wholesome world.

Of course, like any text, poetry is open to interpretation. More so than any other text, in my experience. But contextualizing a poem is just as important. One thing I’ve learned about meaning and interpretation is that the silences speak louder than what is seen. And these silences and hidden codes are what make poetry all the more bewitching than the most obvious meanings we are told.

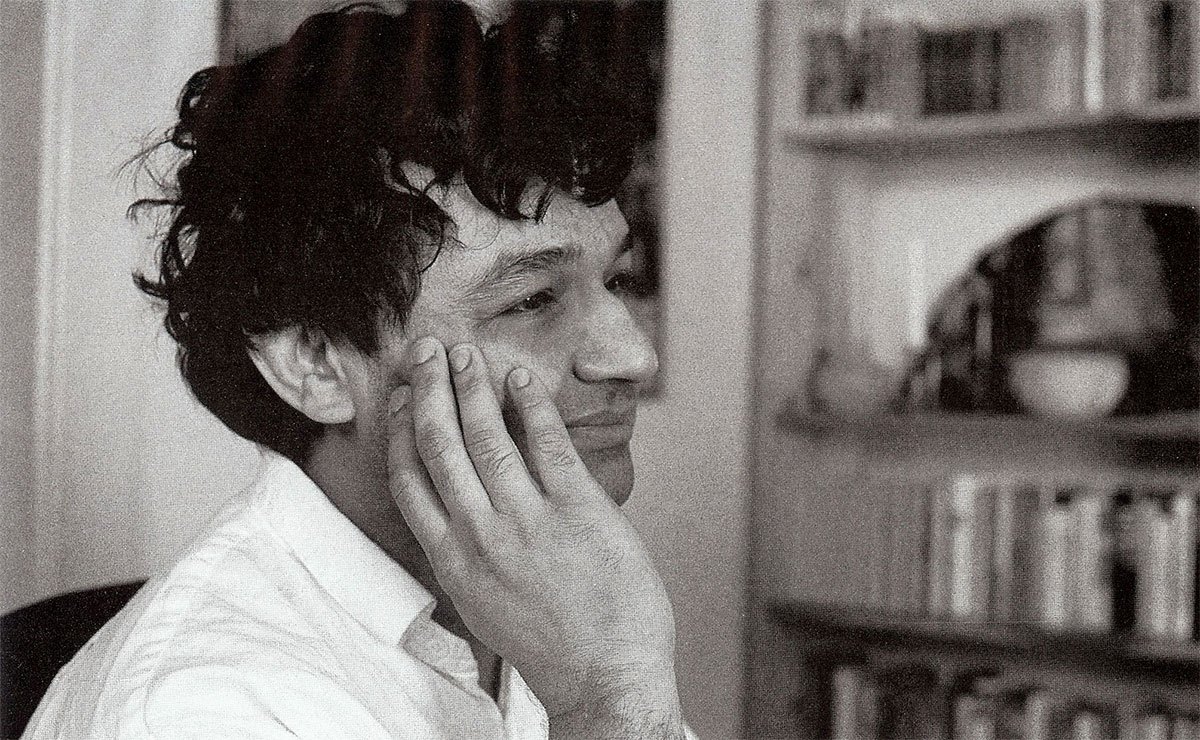

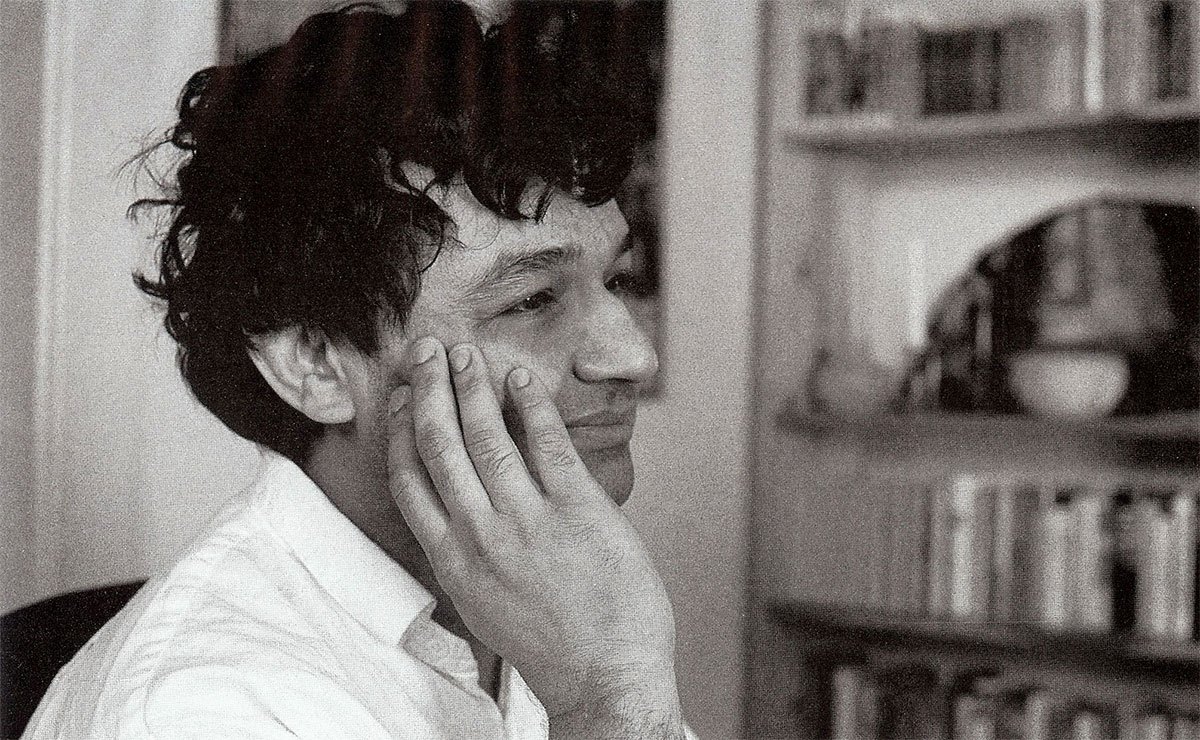

Agha Shahid Ali is one such poet, whose silences and secrets call you in like a siren at sea. He was a gay Muslim man who was born in Delhi, brought up in Kashmir, and later moved to America. His intersectional identity factors heavily in his poems which makes them more raw and captivating. However, the multiplicity in his identity is often ignored and reduced to simply that of nationalism and loyalty to Kashmir. He was controversially named the ‘National Poet of Kashmir’, but in an essay by Amitav Gosh, he declined being called a ‘nationalist’ poet which makes a lot of difference on his identity.

I decided to speak to three of my friends- Meghna, Yashwant, and Parth, who are much bigger fans of Shahid than myself who could tell me more about him as a queer poet. Parth came across Shahid when he was reading Amitav Gosh’s essay on Shahid, The Ghat of the Only World, where he talked about how Shahid was okay with being called a national poet, but not a ‘nationalist’ poet. He says that the ambiguity and the beauty in Shahid’s poems and especially his ghazals are what kept Parth so interested in Shahid.

Meghna said she first came across Shahid in 2003 when she was teaching at Stella Maris College but the first introduction to him did not reveal his queerness. They learnt more about him as they engaged more with him and eventually did her Ph.D. on him. She could connect Shahid and Micheal Ondaatje (a Sri Lankan- Canadian poet) with Salman Rushdie’s notion of the ‘Imaginary Homeland’. “Because my family is all over the place, I don’t really have roots in one place, so I worked on these two writers who have hybrid identities and that’s okay”. What stood out to her was that for someone who doesn’t feel like they belong anywhere, the space of the text itself can be home. Shahid magnified that a lot for her, because the space of poetry is so revolutionary and political, where nothing normative holds.

Yashwant started reading Shahid because of Meghna. She recommended Country Without a Post Office when xe asked for a depressing writer. Yashwant’s personal exploration of pain and suffering inspired xis B.A thesis which was the idea of emotional sadomasochism found in Shahid’s poetry, and also xis Masters dissertation topic on borders (both physical and metaphorical) also based on Shahid’s poetry. Meghna and Yashwant agree that although Kashmir is a prominent presence in his poems, it is not chauvinistically imposed. Rather, Kashmir becomes a place where Shahid is from, but it is not his only identity.

Meghna expressed how Country Without a Post Office, one of Shahid’s most famous works, is so explicitly queer, and yet, people unsee the lover part. The narrative goes that the speaker goes to Kashmir, even though it was a place ridden with violence, looking for his lover. Although missing, he finds letters that were written by his lover that never reached the speaker because there were no postal services to deliver those letters. The speaker says. “...Phantom heart, pray he’s alive. I have returned in the rain to find him, to learn why he never wrote…” and “...I see his voice again: “This is a shrine of words. You’ll find your letters to me. And mine to you…” Meghna adds that for her, the experience of reading the poem is vivid and cinematic in their head like a movie, and this dramatic effect is found throughout his poems, like how he writes, “It’s raining as I write this. I have no prayer. It’s just a shout, held in, it’s Us! It’s Us!”.

She also talked about how much she loves Shahid’s connection to the planet because, for her, ecological spaces are queer because these are spaces where there is no imposition of societal rules and regulations and there is a blurring of the binary between nature/culture; in that no one owns mountains, deserts, the ocean and so on. “Like in the poem Stationary, the desert is seen as a space of liberation for the speaker, and even in Snow in the Desert, the bond between the speaker and the planet is so strong because he is losing things, and so is the planet. There is no need to conform to a certain identity here, one is free to be themselves without judgment.”

Yashwant pointed out how while xe was doing xis dissertation and had to do a literature review, there was little to no material on how Shahid’s poetry is queer. There are mostly only readings of his poems from a nationalist point of view, or interpretations relating to violence and colonization, even though his poems are obviously queer. In reference to Country Without a Post Office, xe found it interesting how Shahid presents the idea of border crossing, how the letters can’t be transported to the speaker, and even if the speaker were able to get the letters, he wouldn’t be able to write back because the lover is missing, so where should the letters go? And it’s the same thing with physical borders as well, we require a passport to cross them depending on how borders and nations are decided.

In Stationary, the act of writing becomes a means of crossing borders and the speaker asks the lover to take elements from nature, like the desert and moonlight, and write to him.

The moon did not become the sun.

It just fell on the desert

In great sheets, reams

of silver handmade by you.

The night is your cottage industry now,

the day is your brisk emporium.

The world is full of paper.

Write to me

~ Agha Shahid Ali

Yashwant said that what happens while interpreting Shahid is that there is an emphasis on nationalism, on physical borders, but his identity as a gay man is completely put aside, even though both these identities are parallel. “People say that since the text is open to interpretation, the author can also be writing from the perspective of a female narrator, like no, don’t rob us of the only few queer poets we have by assuming it’s a female narrator. This is the problem with Indian academia, that stuff on Shahid is so normative that one biography did not even mention the fact that he was gay, and this is shocking and sad and unfair to his works also,” Yashwant lamented.

When I asked why Shahid's queerness was ignored then, Yashwant thinks that it is mostly ignorance on the part of people, and there is also an insistence on focusing on one identity tag at a time, instead of recognizing a multitude of identities coexisting simultaneously. For example, Shahid is a queer Kashmiri-American poet, but people only do a surface reading of him. And it’s also because of the heteronormative structure we live in. Even for Urdu poets like Ghalib, popular interpretations overlook the lack of gender, or how it’s written from a feminine perspective, and the readings done mostly conform to a heteronormative lens. Even though Ghalib is called the Shakespeare of India, people don’t realize that Shakespeare was queer too.

When I asked about how his lover is represented in Shahid’s poetry, Parth says he uses a lot of metaphors from Urdu poetry like the lamb, the moth, the bulbul, a nightingale, and other such images to represent his lover. Yashwant believes that Shahid is very private about whom the poem is dedicated to, so although there is an actual person, it’s not made explicit who that person is or what their relationship is. And in most cases, the speaker and his lover are not destined to be together.

Shahid doesn’t make it explicit in his poems about the speaker’s gender or sexual identity. From what I’ve read (and I haven’t read all of his works yet), the speaker is seen from an ambiguous first-person perspective, and their sexuality and gender aren’t made explicit. And neither is the person the speaker is writing to. We get the sense that the speaker is addressing a lover, but we don’t know who it is. And so, it’s easy for people to assume that the poems depict heterosexual relationships, especially given our socio-political context. Like the phrases “Write to me” or “Phantom heart pray he’s alive,” we don’t know exactly who the speaker is or who is being addressed because no one is named, and their relationship is left to the understanding of the reader.

Parth said he found it interesting that in ghazals, although the predominant theme revolves around a young male lover, there is a lack of an explicit gender or sexuality being assigned, and this ambiguity pushes people to assume things for the poem, which results in subsequent straight-washing. Adding on, Meghna thinks that there shouldn’t be specific queer readings of a poem when the poem is inherently queer. They think that since Shahid is already from a marginalised and controversial space, a queer narrative would be detrimental to the cause of nationalism. “Like in India, we have the problematic category of the “third gender”, but even when it comes to trans people, we don’t often talk about nonbinary or gender fluid people, it’s like a certain kind of queerness is allowed, but not others.” For Meghna, Shahid is someone she goes back to talk about intersectionality and erasure of queer identity.

Yashwant also brought out the idea of ‘strategic essentialism’ which was proposed by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (Indian literary theorist). Xe explains that in Shahid’s case, interpretations mostly look at his roots of him being a Kashmiri, but there is a notion that because they are looking at his roots, they don’t look at his queerness. The point is that Shahid is looking at his roots while also having a queer identity, and his homosexuality cannot be ignored just because he comes from a homophobic culture. When Shahid worked on translating Faiz Ahmed Faiz, another Urdu poet, even though Faiz’s poems were already queer, the translations are further queered because of Shahid’s identity as well. For example, instead of ‘Laila’ in Faiz’s version, Shahid translates it as ‘lover’ which makes it more ambiguous and queer.

Meghna said that one of Shahid’s favourites was Emily Dickinson. She adds that people like Audre Lorde, Shahid, and Dickinson, and even the romantic era poets, have in a way, reinvented the cannon and established a space for queer poetry to blossom, and inspire the present and future generations as well, because there is so much to read in between the lines that mainstream or traditional interpretations don’t capture. So much of poetry has been straight-washed because of political and cultural contexts, that we miss out on queer interpretations because we are taught not to look for them.

When I inquired which poem of Shahid a beginner should begin with, Parth recommended his Ghazals or The Butcher or Stationary, which are his personal favourites. Yashwant recommended Country Without a Post Office. For Meghna as well it was that or The Veiled Suite where interestingly, his lover is presented as a doppelganger. She says that each poem, according to her, reads as a separate narrative instead of a continuation. And based on the context of the poem, the speaker and the lover are different characters.

Personally, when I was reading The Veiled Suite, I think the speaker and his lover are on a time limit for how long they can spend together, and so they meet up in this discreet apartment where they are hidden from the rest of the world. The speaker is desperate to get more time with his lover and so he wants to merge the two of them together to make sure he won’t be forgotten when they part. Shahid is someone you savour and soak in until you are drenched in his misery and his sorrow and his joy - until you forget your own. He is not someone you can breeze through, and his poems speak volumes about queerness, nationalism, colonisation, heteronormativity and so much more that it’s impossible to read him multiple times and not discover new meanings.

The post Agha Shahid Ali: A Lover And A Poet appeared first on Gaysi.

Agha Shahid Ali: A Lover And A Poet

On dark cold days when you seek your lover’s warmth by the window with a cup of tea, or when you feel that aching loneliness of being misunderstood, or when you feel detached from yourself and the pain and the heartache is almost crushing, poetry is the one thing that brings you peace. Poetry makes strangers fall in love, brings friends closer to family, and brings yourself closer to a more wholesome world.

Of course, like any text, poetry is open to interpretation. More so than any other text, in my experience. But contextualizing a poem is just as important. One thing I’ve learned about meaning and interpretation is that the silences speak louder than what is seen. And these silences and hidden codes are what make poetry all the more bewitching than the most obvious meanings we are told.

Agha Shahid Ali is one such poet, whose silences and secrets call you in like a siren at sea. He was a gay Muslim man who was born in Delhi, brought up in Kashmir, and later moved to America. His intersectional identity factors heavily in his poems which makes them more raw and captivating. However, the multiplicity in his identity is often ignored and reduced to simply that of nationalism and loyalty to Kashmir. He was controversially named the ‘National Poet of Kashmir’, but in an essay by Amitav Gosh, he declined being called a ‘nationalist’ poet which makes a lot of difference on his identity.

I decided to speak to three of my friends- Meghna, Yashwant, and Parth, who are much bigger fans of Shahid than myself who could tell me more about him as a queer poet. Parth came across Shahid when he was reading Amitav Gosh’s essay on Shahid, The Ghat of the Only World, where he talked about how Shahid was okay with being called a national poet, but not a ‘nationalist’ poet. He says that the ambiguity and the beauty in Shahid’s poems and especially his ghazals are what kept Parth so interested in Shahid.

Meghna said she first came across Shahid in 2003 when she was teaching at Stella Maris College but the first introduction to him did not reveal his queerness. They learnt more about him as they engaged more with him and eventually did her Ph.D. on him. She could connect Shahid and Micheal Ondaatje (a Sri Lankan- Canadian poet) with Salman Rushdie’s notion of the ‘Imaginary Homeland’. “Because my family is all over the place, I don’t really have roots in one place, so I worked on these two writers who have hybrid identities and that’s okay”. What stood out to her was that for someone who doesn’t feel like they belong anywhere, the space of the text itself can be home. Shahid magnified that a lot for her, because the space of poetry is so revolutionary and political, where nothing normative holds.

Yashwant started reading Shahid because of Meghna. She recommended Country Without a Post Office when xe asked for a depressing writer. Yashwant’s personal exploration of pain and suffering inspired xis B.A thesis which was the idea of emotional sadomasochism found in Shahid’s poetry, and also xis Masters dissertation topic on borders (both physical and metaphorical) also based on Shahid’s poetry. Meghna and Yashwant agree that although Kashmir is a prominent presence in his poems, it is not chauvinistically imposed. Rather, Kashmir becomes a place where Shahid is from, but it is not his only identity.

Meghna expressed how Country Without a Post Office, one of Shahid’s most famous works, is so explicitly queer, and yet, people unsee the lover part. The narrative goes that the speaker goes to Kashmir, even though it was a place ridden with violence, looking for his lover. Although missing, he finds letters that were written by his lover that never reached the speaker because there were no postal services to deliver those letters. The speaker says. “...Phantom heart, pray he’s alive. I have returned in the rain to find him, to learn why he never wrote…” and “...I see his voice again: “This is a shrine of words. You’ll find your letters to me. And mine to you…” Meghna adds that for her, the experience of reading the poem is vivid and cinematic in their head like a movie, and this dramatic effect is found throughout his poems, like how he writes, “It’s raining as I write this. I have no prayer. It’s just a shout, held in, it’s Us! It’s Us!”.

She also talked about how much she loves Shahid’s connection to the planet because, for her, ecological spaces are queer because these are spaces where there is no imposition of societal rules and regulations and there is a blurring of the binary between nature/culture; in that no one owns mountains, deserts, the ocean and so on. “Like in the poem Stationary, the desert is seen as a space of liberation for the speaker, and even in Snow in the Desert, the bond between the speaker and the planet is so strong because he is losing things, and so is the planet. There is no need to conform to a certain identity here, one is free to be themselves without judgment.”

Yashwant pointed out how while xe was doing xis dissertation and had to do a literature review, there was little to no material on how Shahid’s poetry is queer. There are mostly only readings of his poems from a nationalist point of view, or interpretations relating to violence and colonization, even though his poems are obviously queer. In reference to Country Without a Post Office, xe found it interesting how Shahid presents the idea of border crossing, how the letters can’t be transported to the speaker, and even if the speaker were able to get the letters, he wouldn’t be able to write back because the lover is missing, so where should the letters go? And it’s the same thing with physical borders as well, we require a passport to cross them depending on how borders and nations are decided.

In Stationary, the act of writing becomes a means of crossing borders and the speaker asks the lover to take elements from nature, like the desert and moonlight, and write to him.

The moon did not become the sun.

It just fell on the desert

In great sheets, reams

of silver handmade by you.

The night is your cottage industry now,

the day is your brisk emporium.

The world is full of paper.

Write to me

~ Agha Shahid Ali

Yashwant said that what happens while interpreting Shahid is that there is an emphasis on nationalism, on physical borders, but his identity as a gay man is completely put aside, even though both these identities are parallel. “People say that since the text is open to interpretation, the author can also be writing from the perspective of a female narrator, like no, don’t rob us of the only few queer poets we have by assuming it’s a female narrator. This is the problem with Indian academia, that stuff on Shahid is so normative that one biography did not even mention the fact that he was gay, and this is shocking and sad and unfair to his works also,” Yashwant lamented.

When I asked why Shahid's queerness was ignored then, Yashwant thinks that it is mostly ignorance on the part of people, and there is also an insistence on focusing on one identity tag at a time, instead of recognizing a multitude of identities coexisting simultaneously. For example, Shahid is a queer Kashmiri-American poet, but people only do a surface reading of him. And it’s also because of the heteronormative structure we live in. Even for Urdu poets like Ghalib, popular interpretations overlook the lack of gender, or how it’s written from a feminine perspective, and the readings done mostly conform to a heteronormative lens. Even though Ghalib is called the Shakespeare of India, people don’t realize that Shakespeare was queer too.

When I asked about how his lover is represented in Shahid’s poetry, Parth says he uses a lot of metaphors from Urdu poetry like the lamb, the moth, the bulbul, a nightingale, and other such images to represent his lover. Yashwant believes that Shahid is very private about whom the poem is dedicated to, so although there is an actual person, it’s not made explicit who that person is or what their relationship is. And in most cases, the speaker and his lover are not destined to be together.

Shahid doesn’t make it explicit in his poems about the speaker’s gender or sexual identity. From what I’ve read (and I haven’t read all of his works yet), the speaker is seen from an ambiguous first-person perspective, and their sexuality and gender aren’t made explicit. And neither is the person the speaker is writing to. We get the sense that the speaker is addressing a lover, but we don’t know who it is. And so, it’s easy for people to assume that the poems depict heterosexual relationships, especially given our socio-political context. Like the phrases “Write to me” or “Phantom heart pray he’s alive,” we don’t know exactly who the speaker is or who is being addressed because no one is named, and their relationship is left to the understanding of the reader.

Parth said he found it interesting that in ghazals, although the predominant theme revolves around a young male lover, there is a lack of an explicit gender or sexuality being assigned, and this ambiguity pushes people to assume things for the poem, which results in subsequent straight-washing. Adding on, Meghna thinks that there shouldn’t be specific queer readings of a poem when the poem is inherently queer. They think that since Shahid is already from a marginalised and controversial space, a queer narrative would be detrimental to the cause of nationalism. “Like in India, we have the problematic category of the “third gender”, but even when it comes to trans people, we don’t often talk about nonbinary or gender fluid people, it’s like a certain kind of queerness is allowed, but not others.” For Meghna, Shahid is someone she goes back to talk about intersectionality and erasure of queer identity.

Yashwant also brought out the idea of ‘strategic essentialism’ which was proposed by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (Indian literary theorist). Xe explains that in Shahid’s case, interpretations mostly look at his roots of him being a Kashmiri, but there is a notion that because they are looking at his roots, they don’t look at his queerness. The point is that Shahid is looking at his roots while also having a queer identity, and his homosexuality cannot be ignored just because he comes from a homophobic culture. When Shahid worked on translating Faiz Ahmed Faiz, another Urdu poet, even though Faiz’s poems were already queer, the translations are further queered because of Shahid’s identity as well. For example, instead of ‘Laila’ in Faiz’s version, Shahid translates it as ‘lover’ which makes it more ambiguous and queer.

Meghna said that one of Shahid’s favourites was Emily Dickinson. She adds that people like Audre Lorde, Shahid, and Dickinson, and even the romantic era poets, have in a way, reinvented the cannon and established a space for queer poetry to blossom, and inspire the present and future generations as well, because there is so much to read in between the lines that mainstream or traditional interpretations don’t capture. So much of poetry has been straight-washed because of political and cultural contexts, that we miss out on queer interpretations because we are taught not to look for them.

When I inquired which poem of Shahid a beginner should begin with, Parth recommended his Ghazals or The Butcher or Stationary, which are his personal favourites. Yashwant recommended Country Without a Post Office. For Meghna as well it was that or The Veiled Suite where interestingly, his lover is presented as a doppelganger. She says that each poem, according to her, reads as a separate narrative instead of a continuation. And based on the context of the poem, the speaker and the lover are different characters.

Personally, when I was reading The Veiled Suite, I think the speaker and his lover are on a time limit for how long they can spend together, and so they meet up in this discreet apartment where they are hidden from the rest of the world. The speaker is desperate to get more time with his lover and so he wants to merge the two of them together to make sure he won’t be forgotten when they part. Shahid is someone you savour and soak in until you are drenched in his misery and his sorrow and his joy - until you forget your own. He is not someone you can breeze through, and his poems speak volumes about queerness, nationalism, colonisation, heteronormativity and so much more that it’s impossible to read him multiple times and not discover new meanings.

The post Agha Shahid Ali: A Lover And A Poet appeared first on Gaysi.

Post a Comment