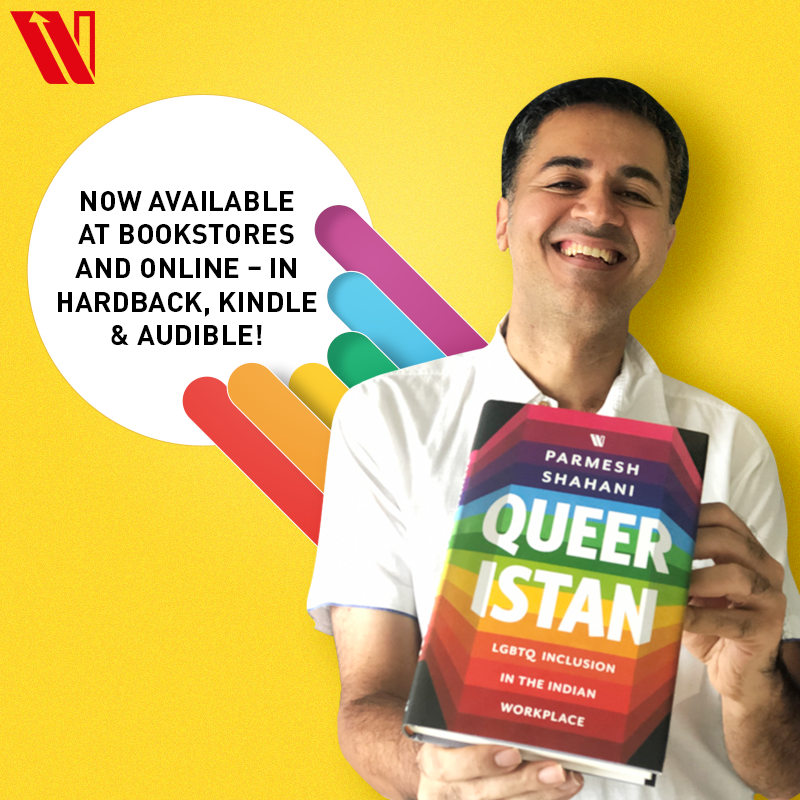

Queeristan by Parmesh Shahani is labeled as a business book, however, it is much more than that. Aptly subtitled ‘LGBTQ Inclusion in the Indian workplace’, it highlights the lags in the Indian corporate with respect to LGTBQ friendly work environments and suggests measures that need to be taken to ensure an inclusive and comfortable workspace for all, irrespective of gender, class and caste. However, it doesn’t restrict itself to being just a business guide but rather contextualizes the need for the book in line with understanding the historical and social realities of the queer community in India. This is Parmesh Shahani’s second book after Gay Bombay: Globalization, Love and (Be)longing in Contemporary India (2008) and here, he extends on his engagement with the queer community and their realities in the Indian context.

The book, although labeled as a business book, reads like part memoir and part manifesto. Shahani doesn’t throw words and concepts in the air, but rather explains them through real-life experience which makes it more believable and practical. Also, unlike other business books, this book doesn’t employ any technical or theoretical linguistic tone; rather, it is conversational and colloquial in nature. We see the use of many anglicized Hindi words and also references to Bollywood in numerous instances. This makes it different from other business books, and makes it easier and entertaining to read even as it imparts valuable information regarding the creation of safe spaces in the workplace.

In 2018, when the Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code was read down, it was a celebratory moment for many who had been working towards creating an inclusive society. However, winning legal battles does not necessarily translate to social changes, especially in a patriarchal and conservative society like India’s. It requires conceited and intentional measures to create a society which is accessible to all equally, and this book rightfully outlines some of the measures which might help create an inclusive atmosphere, at least in the workplace. It is important to note here, that the workplace is the centre of attention in this book and rightfully so. Much of living and sustenance is based on a good working atmosphere, and the Indian workspace is mostly marred with unequal and biased measures, so creating a balanced atmosphere is of utmost need in the present. This book not only outlines the measures that will help create an inclusive workplace, but also provides us with examples of how the author himself has initiated measures and programs in his own workspace to ensure that everyone can access benefits and a safe working environment equally. Here, Shahani is leading by example - rather than just throwing suggestions in the air.

The first section of Queeristan titled ‘This Book Is Personal’ gives us a peek into why the author started the journey of writing his thoughts about the workspace and queerness, and also provides us insight into his own life as an activist and frontrunner of causes related to queerness. The second section, ‘Being LGBTQ in India - An Overview’, historicizes queerness as it has existed throughout the years in India and also provides readers with information on the legal aspects of homosexuality in India. It further tries to suggest to parents and peers about loving and accepting people irrespective of sexual orientation and gender identification. The third section, titled ‘LGBTQ Inclusion Makes Sense, Whichever Way You Look At It’, attempts to present the multiple benefits of creating an LGBTQ friendly atmosphere in the workplace and also outlines how it creates better productivity and better yield, in addition to being a morally justified step. ‘A Five-Step Guide for Making Your Workplace LGBTQ Inclusive’, the fourth section in the book, is the most important section, and directly outlines the steps that companies and individuals need to take to make an inclusive and friendly atmosphere for the LGBTQIA+ community. The fifth and conclusive section is titled ‘Queeristan – A Call to Action’ and presents how a queer-inclusive atmosphere yields change and encourages companies to start on the inclusivity journey as soon as possible.

Shahani stresses upon the need to change the system from within to ensure real-life implications for the queer community. Here, he introduces two important topics – Jugaad Resistance and Cultural Acupuncture. Through Jugaad Resistance, Shahani insists that individuals have to be part of the social structure to change it, and cites his own example of how he made changes in the company he has been working at. Through an interesting linguistic play of words, he presents to us ideas which he believes can make real change in society. The word ‘jugaad’ has often been used in the Indian context for ‘innovations at a lower-cost, and add to that a word as heavy as ‘resistance’ and it brings about a significant relevance. He notes that in order to change a system, one has to be a part of it and hence, creating changes from within starts by being part of the system you would want to change. It is interesting to note here that many activists have opposed capitalism as a mode of exploitation; however, they have not suggested any measures to change the same. Shahani, on the other hand, shows us how we can change the exploitative nature of capitalism and use it to our benefit. He further notes the components of Jugaad Resistance, namely, infiltration and cultural acupuncture. By infiltration, he simply means that one needs to infiltrate or intrude into spaces that have historically excluded certain groups or individuals. For example, Shahani mentions how he used the media to further his agenda of inclusivity and thus used a space that has historically erased or misrepresented the community. Similarly, Cultural Acupuncture is a term used solely for the creation of platforms which could take forward the success of Jugaad Resistance. He mentions that he has derived the word ‘cultural acupuncture’ from the Harry Potter alliance and writes how changemakers within the structures have to create and enable spaces that can further create and solidify an inclusive atmosphere. He specifically cites the example of Godrej India Culture Lab, which was created under Shahani’s supervision, to enable a one-of-a-kind space for everything inclusive and forward-looking.

Another aspect that Shahani puts focus on is the need for anti-discrimination policies at companies to ensure better, less volatile working atmospheres. He mentions how LGBTQ+ employees need special care because of their history of marginalization and violence. He cites numerous examples from the company he worked in, Godrej India, to further present the relevance of these policies. He mentions in one instance how senior leaders at Godrej called for inclusion, and how one of his bosses, Nisaba Godrej, invited ‘partners’ of her employees irrespective of gender for an event. He expresses the joy that it made him feel and calls for such little initiatives which could be significant for queer employees. He also mentions the Godrej Gender Affirmation Policy which helps trans people claim up to Rs 500,000 for non-cosmetic surgeries and Rs 60,000 per year for hormone replacement therapy. He mentions how Godrej One headquarters in Mumbai has two all-gender washrooms. He also reiterates how these little feats call for bigger changes and are a wonderful beginning towards an inclusive and safe workplace. Through these examples, he provides the readers with insights into how to make a better environment for anyone working in any company. Here, rather than just suggesting measures, Shahani again cites real-life examples which make sense to and have a lasting impact on the reader.

What I also loved about the book is how Shahani recognizes his privilege (which most of us, especially authors forget to do). In one of the sections titled ‘Some Thoughts on Privilege’, he details the notion of privilege and how the mic needs to be passed down to the marginalized. He calls against hogging of spaces by privileged people, and stresses upon the need to create spaces for the voiceless. He gives examples of his privilege, and tries to justify how he has helped people by training scholars under him through the Godrej India Culture Lab to use the voice that they have. In another section, he mentions the notion of structures within the queer community, and talks of the layered marginalization in view of class, caste, and other groups. He also calls for intersectionality in discourses, especially when dealing with policies, however, ironically, he mentions his audience in binary terms, such as ‘brother and sister’, rather than a more gender-neutral term. However, we can conceive that as an anecdote for the structures of the real world, where gender continues to be seen in binaries despite severe criticism from activists around the world.

Shahani writes with utmost honesty and transparency, and that is evident with how he talks about the corporate world. He is real and unbiased. Despite writing from the corporate world and about the corporate world, he doesn’t shy away from mentioning its ills. One particular instance that many of us have been talking about is how tokenism fails the cause of inclusivity, especially through the promotion of queer visibility only through representation and not through opportunities. Shahani also touches upon this topic and says how companies use tokenism, especially during Pride Month to further their agenda of inclusivity without any real change in policies to make a better workplace for queer individuals.

Apart from writing about the corporate world, he also details the nitty-gritties of the queer community in India. He talks about the notion of chosen family and of abuse within biological family structure. He cites examples of iconic figures of the Indian queer community who have created space for the present to exist. He mentions the journey of Gauri Sawant, a transgender activist, as an anecdote towards inclusion, and mentions how motherhood is behavior rather than a gender expression. Any discussion on queer issues is incomplete without the discussion of familial structure and motherhood, since the community grapples with these issues on an everyday basis. He mentions in one section how Indian queerness is closely tied to the idea of family and community, and how we are not one self, but many selves - each being conditional and contextual, navigating life according to the situations. He also connects the issue of family to a motivation of having a better workplace because family also becomes a space of identity erasure of many Indian queers. Hence, the workplace becomes the space of negotiating identities, and if a company harbours an LGTBQ+ friendly atmosphere, the person might prosper. He heaps praises on the lawyers Menaka and Aditi, who were two among many to have fought the battle of Section 377 until it was read down. He mentions how important the reading down of Section 377 was and cites the example of the first meeting on UN’s Standards of Conduct for Business focused on LGBTQ inclusion in workplace in 2016 where only 10 companies showed up out of the 30 invited and none of them were publicly ready to acknowledge their presence. He notes that a shift in the attitude of the general public happened after the Section 377 verdict. For a similar meeting at Godrej’s A Manifesto for Trans Inclusion in the Indian Workplace, about 300 business leaders came in and were eager to implement the measures. In this ‘business’ book, he is also educating people about pronouns, and provides a powerful anecdote of Goddess Durga to explain the concept of they/them in reference to the Hindi word ‘Aap (??)’. The book is a balanced view of the personal experiences of the author and the political need of the hour. Shahani successfully manages to take the reader through a historical account of queer visibility in India, the efforts made by icons to ensure a present, the present successes and lags that need to be filled and also the ways to make the future better. In a conversational tone, Shahani manages to also hold the attention of the reader and make it an entertaining read through episodes like his endearing love story at Kasish 2016. Although he does the work that the book intended to, which is suggesting measures about making queer-friendly workspace, he also presents a rounded outlook of queer visibility and queer social reality in India. Indian queerness, to him, is circulatory and not something formed out of tension between the global and the local. It is ever-evolving. Shahani also doesn’t shy away from engaging with political intolerance in India and mentions the social, economic and political differences that play out as everyday realities. Shahani’s Queeristan is an important book and not only because it suggests measures for a better future; it gives us an insight into a world (that of Shahani’s and his company, Godrej India) which is inclusive and equal and so, hopeful and promising! It is a must-read odyssey of the Indian corporate and its potential.

The post Parmesh Shahani’s Queeristan: An Entertaining And Enlightening Peek Into The Indian Corporate And Queerness! appeared first on Gaysi.

Parmesh Shahani’s Queeristan: An Entertaining And Enlightening Peek Into The Indian Corporate And Queerness!

Queeristan by Parmesh Shahani is labeled as a business book, however, it is much more than that. Aptly subtitled ‘LGBTQ Inclusion in the Indian workplace’, it highlights the lags in the Indian corporate with respect to LGTBQ friendly work environments and suggests measures that need to be taken to ensure an inclusive and comfortable workspace for all, irrespective of gender, class and caste. However, it doesn’t restrict itself to being just a business guide but rather contextualizes the need for the book in line with understanding the historical and social realities of the queer community in India. This is Parmesh Shahani’s second book after Gay Bombay: Globalization, Love and (Be)longing in Contemporary India (2008) and here, he extends on his engagement with the queer community and their realities in the Indian context.

The book, although labeled as a business book, reads like part memoir and part manifesto. Shahani doesn’t throw words and concepts in the air, but rather explains them through real-life experience which makes it more believable and practical. Also, unlike other business books, this book doesn’t employ any technical or theoretical linguistic tone; rather, it is conversational and colloquial in nature. We see the use of many anglicized Hindi words and also references to Bollywood in numerous instances. This makes it different from other business books, and makes it easier and entertaining to read even as it imparts valuable information regarding the creation of safe spaces in the workplace.

In 2018, when the Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code was read down, it was a celebratory moment for many who had been working towards creating an inclusive society. However, winning legal battles does not necessarily translate to social changes, especially in a patriarchal and conservative society like India’s. It requires conceited and intentional measures to create a society which is accessible to all equally, and this book rightfully outlines some of the measures which might help create an inclusive atmosphere, at least in the workplace. It is important to note here, that the workplace is the centre of attention in this book and rightfully so. Much of living and sustenance is based on a good working atmosphere, and the Indian workspace is mostly marred with unequal and biased measures, so creating a balanced atmosphere is of utmost need in the present. This book not only outlines the measures that will help create an inclusive workplace, but also provides us with examples of how the author himself has initiated measures and programs in his own workspace to ensure that everyone can access benefits and a safe working environment equally. Here, Shahani is leading by example - rather than just throwing suggestions in the air.

The first section of Queeristan titled ‘This Book Is Personal’ gives us a peek into why the author started the journey of writing his thoughts about the workspace and queerness, and also provides us insight into his own life as an activist and frontrunner of causes related to queerness. The second section, ‘Being LGBTQ in India - An Overview’, historicizes queerness as it has existed throughout the years in India and also provides readers with information on the legal aspects of homosexuality in India. It further tries to suggest to parents and peers about loving and accepting people irrespective of sexual orientation and gender identification. The third section, titled ‘LGBTQ Inclusion Makes Sense, Whichever Way You Look At It’, attempts to present the multiple benefits of creating an LGBTQ friendly atmosphere in the workplace and also outlines how it creates better productivity and better yield, in addition to being a morally justified step. ‘A Five-Step Guide for Making Your Workplace LGBTQ Inclusive’, the fourth section in the book, is the most important section, and directly outlines the steps that companies and individuals need to take to make an inclusive and friendly atmosphere for the LGBTQIA+ community. The fifth and conclusive section is titled ‘Queeristan – A Call to Action’ and presents how a queer-inclusive atmosphere yields change and encourages companies to start on the inclusivity journey as soon as possible.

Shahani stresses upon the need to change the system from within to ensure real-life implications for the queer community. Here, he introduces two important topics – Jugaad Resistance and Cultural Acupuncture. Through Jugaad Resistance, Shahani insists that individuals have to be part of the social structure to change it, and cites his own example of how he made changes in the company he has been working at. Through an interesting linguistic play of words, he presents to us ideas which he believes can make real change in society. The word ‘jugaad’ has often been used in the Indian context for ‘innovations at a lower-cost, and add to that a word as heavy as ‘resistance’ and it brings about a significant relevance. He notes that in order to change a system, one has to be a part of it and hence, creating changes from within starts by being part of the system you would want to change. It is interesting to note here that many activists have opposed capitalism as a mode of exploitation; however, they have not suggested any measures to change the same. Shahani, on the other hand, shows us how we can change the exploitative nature of capitalism and use it to our benefit. He further notes the components of Jugaad Resistance, namely, infiltration and cultural acupuncture. By infiltration, he simply means that one needs to infiltrate or intrude into spaces that have historically excluded certain groups or individuals. For example, Shahani mentions how he used the media to further his agenda of inclusivity and thus used a space that has historically erased or misrepresented the community. Similarly, Cultural Acupuncture is a term used solely for the creation of platforms which could take forward the success of Jugaad Resistance. He mentions that he has derived the word ‘cultural acupuncture’ from the Harry Potter alliance and writes how changemakers within the structures have to create and enable spaces that can further create and solidify an inclusive atmosphere. He specifically cites the example of Godrej India Culture Lab, which was created under Shahani’s supervision, to enable a one-of-a-kind space for everything inclusive and forward-looking.

Another aspect that Shahani puts focus on is the need for anti-discrimination policies at companies to ensure better, less volatile working atmospheres. He mentions how LGBTQ+ employees need special care because of their history of marginalization and violence. He cites numerous examples from the company he worked in, Godrej India, to further present the relevance of these policies. He mentions in one instance how senior leaders at Godrej called for inclusion, and how one of his bosses, Nisaba Godrej, invited ‘partners’ of her employees irrespective of gender for an event. He expresses the joy that it made him feel and calls for such little initiatives which could be significant for queer employees. He also mentions the Godrej Gender Affirmation Policy which helps trans people claim up to Rs 500,000 for non-cosmetic surgeries and Rs 60,000 per year for hormone replacement therapy. He mentions how Godrej One headquarters in Mumbai has two all-gender washrooms. He also reiterates how these little feats call for bigger changes and are a wonderful beginning towards an inclusive and safe workplace. Through these examples, he provides the readers with insights into how to make a better environment for anyone working in any company. Here, rather than just suggesting measures, Shahani again cites real-life examples which make sense to and have a lasting impact on the reader.

What I also loved about the book is how Shahani recognizes his privilege (which most of us, especially authors forget to do). In one of the sections titled ‘Some Thoughts on Privilege’, he details the notion of privilege and how the mic needs to be passed down to the marginalized. He calls against hogging of spaces by privileged people, and stresses upon the need to create spaces for the voiceless. He gives examples of his privilege, and tries to justify how he has helped people by training scholars under him through the Godrej India Culture Lab to use the voice that they have. In another section, he mentions the notion of structures within the queer community, and talks of the layered marginalization in view of class, caste, and other groups. He also calls for intersectionality in discourses, especially when dealing with policies, however, ironically, he mentions his audience in binary terms, such as ‘brother and sister’, rather than a more gender-neutral term. However, we can conceive that as an anecdote for the structures of the real world, where gender continues to be seen in binaries despite severe criticism from activists around the world.

Shahani writes with utmost honesty and transparency, and that is evident with how he talks about the corporate world. He is real and unbiased. Despite writing from the corporate world and about the corporate world, he doesn’t shy away from mentioning its ills. One particular instance that many of us have been talking about is how tokenism fails the cause of inclusivity, especially through the promotion of queer visibility only through representation and not through opportunities. Shahani also touches upon this topic and says how companies use tokenism, especially during Pride Month to further their agenda of inclusivity without any real change in policies to make a better workplace for queer individuals.

Apart from writing about the corporate world, he also details the nitty-gritties of the queer community in India. He talks about the notion of chosen family and of abuse within biological family structure. He cites examples of iconic figures of the Indian queer community who have created space for the present to exist. He mentions the journey of Gauri Sawant, a transgender activist, as an anecdote towards inclusion, and mentions how motherhood is behavior rather than a gender expression. Any discussion on queer issues is incomplete without the discussion of familial structure and motherhood, since the community grapples with these issues on an everyday basis. He mentions in one section how Indian queerness is closely tied to the idea of family and community, and how we are not one self, but many selves - each being conditional and contextual, navigating life according to the situations. He also connects the issue of family to a motivation of having a better workplace because family also becomes a space of identity erasure of many Indian queers. Hence, the workplace becomes the space of negotiating identities, and if a company harbours an LGTBQ+ friendly atmosphere, the person might prosper. He heaps praises on the lawyers Menaka and Aditi, who were two among many to have fought the battle of Section 377 until it was read down. He mentions how important the reading down of Section 377 was and cites the example of the first meeting on UN’s Standards of Conduct for Business focused on LGBTQ inclusion in workplace in 2016 where only 10 companies showed up out of the 30 invited and none of them were publicly ready to acknowledge their presence. He notes that a shift in the attitude of the general public happened after the Section 377 verdict. For a similar meeting at Godrej’s A Manifesto for Trans Inclusion in the Indian Workplace, about 300 business leaders came in and were eager to implement the measures. In this ‘business’ book, he is also educating people about pronouns, and provides a powerful anecdote of Goddess Durga to explain the concept of they/them in reference to the Hindi word ‘Aap (??)’. The book is a balanced view of the personal experiences of the author and the political need of the hour. Shahani successfully manages to take the reader through a historical account of queer visibility in India, the efforts made by icons to ensure a present, the present successes and lags that need to be filled and also the ways to make the future better. In a conversational tone, Shahani manages to also hold the attention of the reader and make it an entertaining read through episodes like his endearing love story at Kasish 2016. Although he does the work that the book intended to, which is suggesting measures about making queer-friendly workspace, he also presents a rounded outlook of queer visibility and queer social reality in India. Indian queerness, to him, is circulatory and not something formed out of tension between the global and the local. It is ever-evolving. Shahani also doesn’t shy away from engaging with political intolerance in India and mentions the social, economic and political differences that play out as everyday realities. Shahani’s Queeristan is an important book and not only because it suggests measures for a better future; it gives us an insight into a world (that of Shahani’s and his company, Godrej India) which is inclusive and equal and so, hopeful and promising! It is a must-read odyssey of the Indian corporate and its potential.

The post Parmesh Shahani’s Queeristan: An Entertaining And Enlightening Peek Into The Indian Corporate And Queerness! appeared first on Gaysi.

Post a Comment